[First, a little housecleaning: I am currently looking for Creative Director/ Copywriter freelance or full-time opportunities. My portfolio, for reference, can be seen here. If you’ve got a tip, please reach out to arye@aryedworken.com. Now, on with our program]

The older I get, the more I relate to Walter White.

This is not to say I'm considering renting an RV and manufacturing meth from my driveway, but as my career moves further along toward the precipice of irrelevance, I think about my future as a provider and nothing seems out of the realm of consideration.

Like Walter standing at the front of his classroom—brilliant but overlooked, his potential calcifying into frustration—I understand the gravitational pull of desperation. After all, before his descent into criminal enterprise, White also represented something uncomfortably familiar to many of us in mid-career: a man who once showed tremendous promise, who had colleagues go on to extraordinary success (in his case, a Nobel Prize), while he remained stuck teaching disinterested high school students who couldn't care less about the periodic table. His skills were specific, his options limited, his trajectory flat. Until crisis forced his hand.

When Breaking Bad first aired in 2008, I cycled through a gamut of emotions watching Walt's descent—disgust at his violence, harsh judgment of his choices, frustration at his pride-driven mistakes. I viewed his transformation with the comfortable moral clarity of someone who'd never looked down an existential crossroads. But something has shifted in retrospect. I find myself less judgmental now, more understanding of the impossible decisions he felt forced to make. Which is, frankly, an insane thing to consider—that I can watch a man dissolve bodies in acid and think, "I see how he got there." The line between righteous indignation and uncomfortable recognition has blurred, not because I've grown more callous, but because the distance between ordinary professional anxiety and existential discombobulation feels shorter than it once did.

I have invested over twenty years into the advertising industry and it was my hope to invest into it another twenty more. I even remember when I decided to become a copywriter–it happened in my high school junior year when I was commissioned by my friends to develop campaign slogans for class elections. I even developed one for myself–”if anyone can, Dworken” (I won, by the way).

But now, I'm witnessing an industry-wide transformation that would have been unimaginable even five years ago. Corporate agency heads are drooling over AI and cheering its progress from the sidelines like parents witnessing their child's first steps. Media buying that once supported entire departments now happens through beep-boop-beep automated platforms. The specialized knowledge that built careers and agencies is being flattened and undervalued as if accumulated experience were to a person's detriment.

Yet, this isn't about individual obsolescence—it's about watching the very foundation of industries crack and shift beneath our feet as we're left wondering if the expertise we've developed still matters in a landscape being rewritten by algorithms, automation, and artificial intelligence.

Spend a few minutes scrolling on LinkedIn and you'll discover a social platform that manifests the madcap energy of a corporate asylum. Panic permeates what was once a professional networking site, now transformed into a bizarre theater of performative career enthusiasm, humblebrags disguised as vulnerability, and uncomfortably personal inspiration porn. Between the "I'm happy to announce" posts and contrived stories of triumph over minor inconveniences, there seems to be an coordinated effort to justify the thing we've invested so many years into, as if irrelevance were a shark smelling the blood of our vulnerability and every self-promoting post is just another desperate attempt to stay afloat.

Incidentally, my most viral post on LinkedIn which I posted the other day read, “man, there’s gotta be a better way to find jobs than this platform.”

If I had a nickel for every time someone I knew shared a link to this weekend’s New York Times article titled “The Gen X Career Meltdown,” I would have had enough to not worry about a career meltdown. The story written by Steven Kurutz profiled a rotating cast of creative individuals in different industries–photographer, music journalist, film director, an advertising creative, etc. I even recognized one of the names–I used to pitch Steve Kandell stories when he was an editor at Spin.

But Kandell aside, the rest weren't just anonymous profiles. These were my contemporaries—a generation caught in the crosshairs of technological disruption and economic uncertainty. The article read like a collective confession, each subject articulating the unspoken anxiety that has been simmering just beneath the surface of our professional lives. Peter Wilcha's pivot from documentary filmmaker to commercial director, then back again, mirrored the kind of professional gymnastics that exhausted me just reading about it. It wasn't about selling out anymore; it was about survival.

The "what now?" Kurutz poses in giant font midway through the article wasn't just a question—it was a generational mantra. We were the generation wedged between the analog world and the digital revolution, watching our carefully constructed professional identities fragmenting faster than a Napster download interrupted by a screeching AOL dial-up connection [the real ones know].

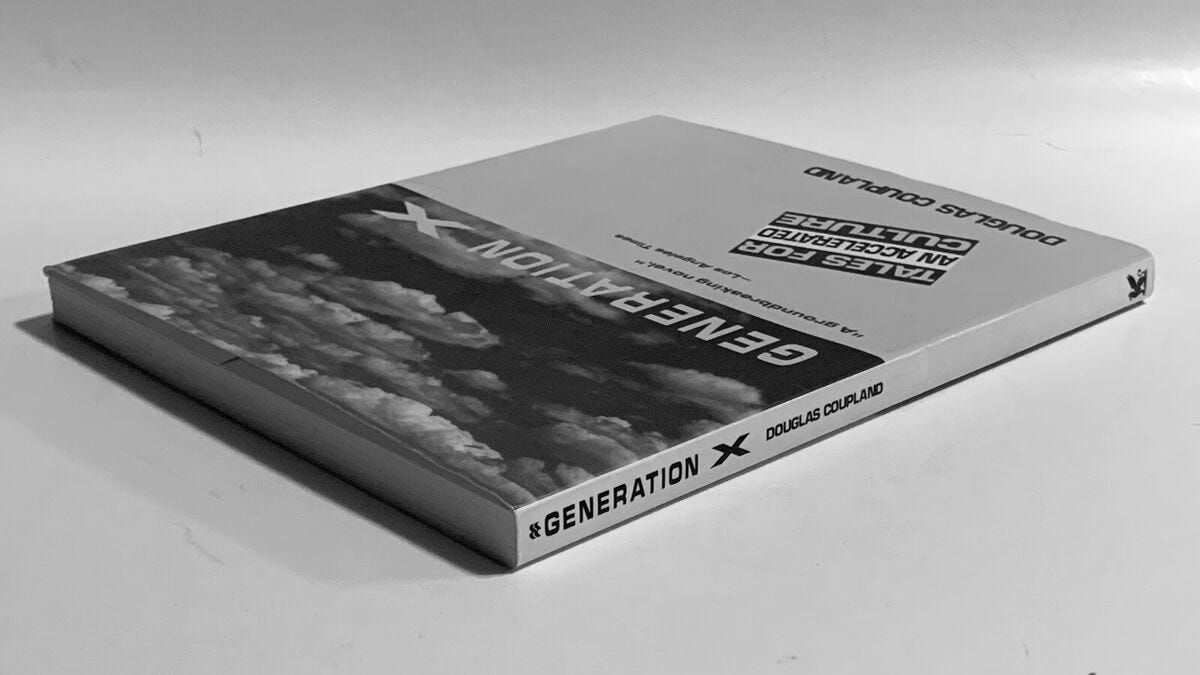

Decades ago, author Douglas Coupland diagnosed our generational malaise before most of us even recognized it was a condition. In Generation X, he mapped out the emotional topography of an age group that never expected to inherit the professional promises of our parents—suburban stability, linear career trajectories, the comfortable mythology of upward mobility. We were always the asterisk, the footnote, the generation perpetually waiting in the wings. Now, reading Kurutz's article, which references Generation X, Coupland's prophetic vision feels less like cultural criticism and more like an instruction manual for professional survival.

Take Andy, Claire, and Dag—the novel's protagonists.These weren't just characters. They were archetypes of professional resistance. Andy's job "historical negative" was essentially a glorified data entry position where he would remove people from group photos—a metaphorical erasure that mirrors how many of us now feel about our own professional identities in an age of algorithmic replacement. Claire's approach to work—fragmenting her labor between temp jobs and creative pursuits—predates the gig economy by decades. And Dag, with his constant job-hopping and deliberate underemployment, looks like a prototype of today's freelance culture, where survival means constant reinvention.

Coupland understood something fundamental: for our generation, job security was always going to be a myth. The characters in Generation X didn't dream of climbing corporate ladders. They built escape routes. They constructed entire philosophies around avoiding the traditional markers of professional success. Now, reading the New York Times article, it feels like those escape routes have become our main highways. The only difference is that at the time of the book’s release, rent for a one bedroom in New York City costs $800, and a pint of beer cost $2.00. Which meant you could survive on $1,500 a month depending on your beer intake. Whereas the average monthly expenses for a Gen X family (typically ages 44-59 in 2024) can be $7,500. And a beer on tap can cost you as much as $10.

I remember working at another coveted agency assigned to a high profile client where I encountered a supervisor who had elevated passive-aggressiveness to an art form. He would sometimes demand that I sit at my desk long after hours, not because there was actual work to be done, but because "showing initiative" was some mystical professional incantation. He explained that it showed initiative and that there would be a possibility that my skills would come into play. I also recently had my first child.

Something shifted inside me during those endless hours concepting digital banners for Walmart. Time seemed to slip away, twelve hours a day dissolving into promotions and brand guidelines. I began to understand the quiet desperation of compromise—how dreams don't die in dramatic explosions, but in incremental surrenders.

Looking back on my career, I also see a curious pattern emerging. Many of the people I've worked alongside over the years have gone on to become Chief Creative Officers, Chief Marketing Officers, founders of their own companies. There's a part of me that wants to believe in something I've half-jokingly called the "Dworken Bump"—that my early collaborations might have sparked something in them. But the more honest part of me knows they made the choices they made. They chose a different path. I chose intentional balance, a work-life harmony that the industry would only begin to value and advocate for a decade later.

Do I regret these decisions? The answer isn't simple. Some days, scrolling through LinkedIn, I catch myself sliding into that dangerous comparison game—measuring my professional trajectory against the curated success stories of former colleagues. An old partner and creative collaborator seems to have ascended the industry ladder with a kind of effortless precision that can trigger momentary doubt. Yet I remember his own declarations from years ago, how advertising was always meant to be a temporary stop, a stepping stone to something more "meaningful"—like becoming a school teacher. I wonder if, in those quiet moments when he drops his child off at school, he's wrestling with his own set of what-ifs.

But the midlife mind is complex and wrestles with mortality in unexpected ways. Recently, an advertising luminary passed away at an age that felt uncomfortably close to my own—a stark reminder of life's fragile timeline. I didn't know him personally, but his obituaries painted a portrait of a complicated creative spirit: a man who championed brilliant work, sometimes at the expense of personal relationships. He was familiar to me—a type I'd encountered countless times in my career, equal parts visionary and difficult.

Yet something pulled me into the depths of his story. Perhaps it was our shared demographics—Jewish, father of three, roughly the same age—or perhaps it was the existential vertigo of seeing a peer's entire professional life distilled into frequent references to a viral marketing stunt he'd created for a candy company. Is that what defines our professional legacy? A clever bit of consumerism that momentarily captured public attention before dissolving into the digital ether?

The irony isn't lost on me that Gen X was raised to view selling out as the ultimate betrayal, yet we now navigate a landscape where authenticity itself is the primary currency. We entered adulthood believing in a clear moral distinction between artistic integrity and commercial compromise, only to watch as the entire culture transformed into one giant sponsored content opportunity. No wonder we struggle with this corporate landscape – we're still processing the cognitive dissonance of a world where everyone is simultaneously creating their personal brand while performing authenticity.

Perhaps Gen X's real lament isn't just relegated to a difficult job market, but it's bearing witness to the Times of the Before and the After. We entered a workforce where compromising your values for commercial gain carried real stigma—where Kurt Cobain could wear a "Corporate magazines still suck" t-shirt on the cover of Rolling Stone and it felt like rebellion, not irony. Then came the digital revolution, dissolving the boundaries between personal and professional, between authentic expression and brand positioning, between art and commerce. We've watched as social media transformed every aspect of life into content to be monetized, as algorithms replaced human judgment, as the gig economy repackaged precarity as freedom. Now we find ourselves navigating a bizarre landscape where authenticity itself has become the most valuable commodity to sell. No wonder we're experiencing a collective existential crisis. It's not just that the rules changed; it's that the very concept of rules—the possibility of standing outside the marketplace—has vanished entirely. We're not obsolete. We're witnesses to a transformation so profound that we haven't yet found the language to describe it. And for a generation that placed so much value on authentic human expression, being left wordless might be the most terrifying part of all.