When I was a kid, every Friday, my father would take me to the comic book store to stock up on that week's latest releases. As a non-athletic adolescent who also underperformed as a student, comics offered me an escape from the mundanity of everyday life. Yes, I was what many would designate an OG, or "original geek," but back then, being a geek was a fairly lonely, isolated experience, never mind, interacting with the opposite sex. Let's just say my encyclopedic knowledge of the Green Lantern Corps wasn't exactly the aphrodisiac I'd hoped it would be.

Yet some of my favorite memories involve reading comics alone in my room while music blared from a Casio double cassette radio (most likely Rush). Which makes it exponentially more surreal now living in a world where the thing I obsessed over in my Fortress of Solitude is a globally shared experience generating billions yearly.

In fact, just last week, I had my hair washed by a 6'2" slender blonde who could have passed for Miss Universe from some Eastern European country. When she asked about my collectibles (I was outed by my hairdresser), I discovered Miss Belarus considered herself a huge Marvel fan. Being a "Marvel fan" isn't so much a choice anymore as it is an inevitability—like catching Covid—but for a moment, I was certain I was experiencing a glitch in the Matrix. Women who look like her weren't supposed to like superheroes. It felt unnatural, as if she were a secret agent working undercover, her knowledge of comics nothing more than reconnaissance gleaned from my personal dossier.

That discomfort revealed something important: my relationship with comics was fundamentally shaped by their status as outsider art. Comics were once a refuge for people on society's margins—the awkward, the different, the ones who didn't quite fit in. As superheroes have conquered the global box office, they've necessarily moved further from their source material's intentions. And in doing so, they may be sacrificing what made them meaningful in the first place.

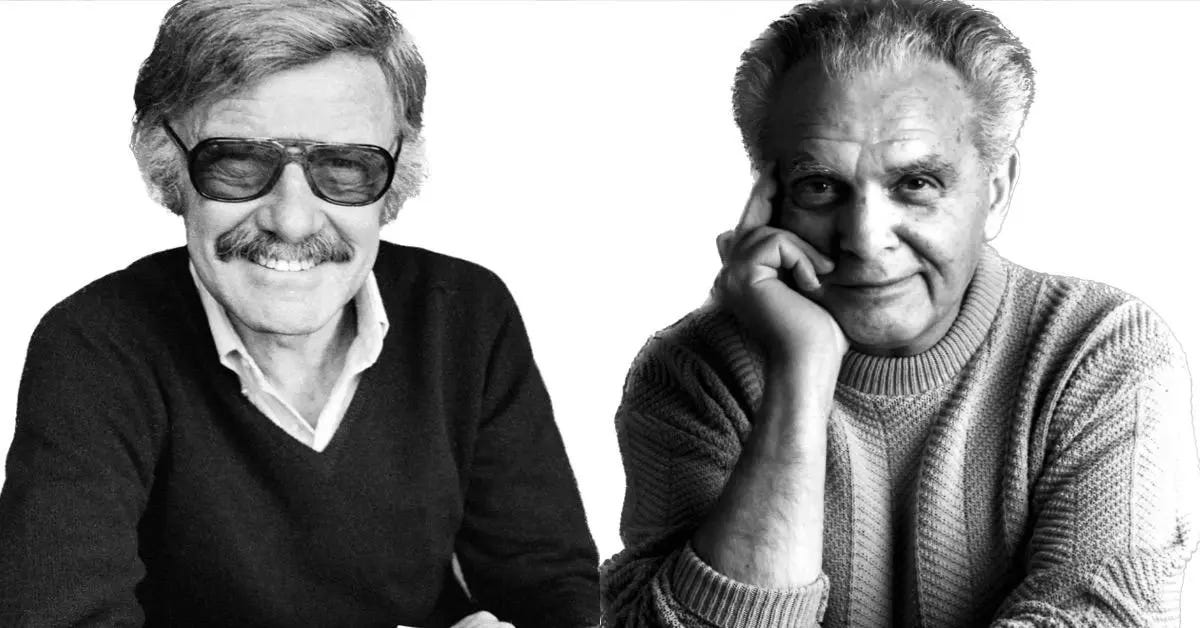

What we often forget is that most superhero creators conceived these characters as means of processing their own otherness. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, children of Jewish immigrants, created Superman when the world was contending with growing anti-Semitism. Stan Lee (born Stanley Lieber) invented an allegory about discrimination with the X-Men, possibly exploring what it meant to be Jewish in a primarily Christian suburb in the 1960s.

These weren't just caped crusaders punching bad guys. They were complex allegories allowing creators and readers to process feelings of exclusion while operating within moral frameworks that were more widely shared than they are today. It may seem hard to remember, but there once was a time when everyone agreed Nazis were bad. Captain America could punch Hitler on his comic cover precisely because the evil of Nazism wasn't a contested concept.

This ability to explore otherness wasn't coincidental—it was directly enabled by comics' own status as cultural outsiders. Part of what gave comics their energy was precisely that they weren't considered "proper entertainment." Rejected by the mainstream, creators worked with remarkable freedom. They could be political, experimental, even occasionally awful. Another advantage of this outsider status was that comics could take clear moral positions without worrying about alienating half their potential audience.

Today's superhero stories strain under the weight of mainstream acceptance and global market pressures. When studios invest $200 million in a film, creative decisions become financial calculations—what will appeal to the widest possible audience without alienating potential ticket buyers? This commercial reality forces compromises that earlier comics never had to make.

Consider Magneto, the X-Men's arch-nemesis. Lee and Kirby created him as a Jewish Holocaust survivor who swore "never again," defending fellow mutants because of his traumatic experiences. Writer Chris Claremont even explicitly modeled the character on Israeli leader Menachem Begin. Yet rumors now circulate that Marvel is considering casting Denzel Washington in the role—a brilliant actor whose casting would nevertheless fundamentally alter a character whose specific historical trauma shapes his entire worldview. In erasing Magneto's Jewishness, we wouldn't just be changing a character—we'd be severing the very historical roots that gave his rage meaning and moral weight.

Iron Man, the first film in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, came out in 2008. The world was very different then. Escapism felt like a personal endeavor, not a global imperative. The cultural atmosphere still felt less heavy than it does now.

When stories created by outsiders for outsiders become mainstream entertainment, the very qualities that made them resonant for their original audience often get watered down. The sharp edges get sanded off; the specific cultural contexts get universalized; the moral certainties become ambiguous. What's left might be entertaining, but it lacks the bite that made the original material so powerful.

Today's superheroes exist in a cultural landscape where nothing seems universally agreed upon. The creatives behind these stories appear to be trying to convince audiences of their own sense of morality rather than appealing to shared values. But in our current times, this sense of truth doesn't exist in the same way. Nothing is black and white. Everything is gray. You're wrong. I'm right.

This fear of alienating audiences has never been more apparent than in the recent Captain America: Brave New World. Despite featuring Anthony Mackie as Sam Wilson, the first Black Captain America—ostensibly a progressive milestone—the film never commits to anything substantive. It gestures toward addressing racial tensions and political polarization, but retreats into generic action sequences whenever these themes demand real confrontation. Even its central conflict—a MAGA-inspired president who transforms into the Red Hulk—is sanitized of meaningful political commentary (don’t even get me started about Sabra).

This kind of hedging is precisely what the original comics—at their best—didn't do. They took stands. They had points of view. They weren't afraid to alienate readers who disagreed with their politics because they weren't trying to be all things to all people.

The irony is that the best superhero stories have always contained moral complexity. What they didn't do was hedge on fundamental questions of right and wrong. Today's superhero stories, desperate to appeal to everyone, end up saying nothing of substance to anyone.

What made older comics effective was their allegorical nature. While the X-Men were incidentally Jewish or gay or Black, they were foremost mutants, a fictional category serving as a vessel for any reader's experience of otherness. This created powerful universality through specificity: by not being explicitly about any one marginalized group, they could be about all of them.

Today's comics landscape looks different. We have more explicitly marginalized characters than ever—heroes who are openly gay, non-binary, Latinx, and more. This seems like progress. Yet these characters often struggle to find an audience. Sales for their books lag behind traditional heroes, and screen adaptations frequently underperform (America Chavez, Riri Williams, and Miss Marvel come to mind).

Many progressive commentators attribute this to bigotry. But this explanation feels reductive. After all, the X-Men—a thinly veiled allegory for civil rights—became one of the most successful comic franchises in history. Perhaps it's the approach. When Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, and Chris Claremont addressed otherness and morality, they did so through metaphor and allegory. Today's more literal approach might actually be undermining its own goals.

Is escapism still impactful when it becomes so closely representative of our world? Perhaps the power of escapist fiction lies precisely in its ability to transport us somewhere different, creating distance that allows us to process real-world concerns through metaphor rather than direct representation.

When representation becomes this literal, it may do the opposite of what's intended. It silos people behind heroes resembling their exact identities, rather than allowing them to find characters that connect viscerally for unexplained reasons. Similarly, when superhero stories try to explicitly validate every possible moral and political perspective, they end up validating none of them.

Yes, there's something undeniably wonderful about all three of my children knowing She-Hulk's real name. There's something validating about Miss Belarus asking to see my collection. But mainstream success has also created an unsolvable paradox. The very qualities that made superhero stories resonant—their ability to speak from the margins, to process otherness through metaphor, to be weird and political and occasionally messy, to take clear moral positions—become liabilities when billions of dollars are at stake.

I often find myself thinking about those Friday afternoons at the comic book store, that quiet bedroom with Rush playing in the background. What I valued wasn't the obscurity of comics but their ability to speak directly to my experience of not belonging—to make me feel seen in a world that often left me feeling invisible.

And when that happens, I wonder about my younger self in today's world, where those once-private journeys have become globally shared experiences. Would his mind be blown that his secret language was spoken by so many? Would he have felt less alone, knowing millions shared his passion?

Or would something essential have been lost—that intimate feeling of discovering a world that seemed to exist just for him, speaking directly to his experience of difference? Would these stories have meant as much if they hadn't been his to discover in quiet solitude?

As it turns out, I got the world I thought I yearned for during those isolated moments: one where comic books are taken seriously and superheroes dominate our cultural conversation. But I suspect my younger self would have sensed, even amid that validation, that something irreplaceable was lost in the translation from margin to mainstream—the sacred refuge these stories once provided to those of us who had nowhere else to go.

Things I’m Enjoying This Week

Lady Gaga's Mayhem

At the Screen Actors Guild Awards, Timothée Chalamet declared, "I'm really in pursuit of greatness." I imagine Gaga watching miles away nodding in recognition as a kindred spirit. This relentless ambition courses through her seventh album, where she continues her career-long pattern of swinging for the fences.

Mayhem delivers on this bold vision, standing as her strongest collection in years. The album traverses decades of sonic influence with stunning confidence—from the chaotic club anthem "Abracadabra" to the Erasure-adjacent 80's synth-pop of "How Bad Do U Want Me" to the Gesaffelstein-assisted "Killah," a slice of future-funk that could have slipped off Prince's 1989 Batman soundtrack. Mayhem is gloriously manic and, true to its title, controlled mayhem.

But beneath the genre-hopping experimentation, as Gaga herself acknowledges on the album's fourth track, is her ultimate form as "your perfect celebrity." Looking at the full spectrum of her career—the meat dresses, jazz standards, Oscar-winning ballads, and now this triumphant return to pop maximalism—it's hard to disagree.

Mickey 17 (Dir. Bong Joon-ho)

It's been a long time since I left a theater genuinely unsure of how I felt. This isn't to say Bong Joon-ho's Mickey 17 is bad—it's undeniably challenging. The film packs so many themes into its one hundred and thirty-seven minutes that I'm not convinced I've grasped them all: animal cruelty, fascism, artificial intelligence, genetic ethics, the ruinous allure of media. Any one of these ideas could sustain its own film, yet Director Bong (as he's known in his native Korea) blends them together into a special sauce—a reference that will make sense once you see the movie.

I admire his ambition, even if I'm not entirely sure it coheres. What does work without question is Robert Pattinson's performance. He may be the crush du jour of my two daughters, but his work here is admirably odd and committed. Whatever your feelings about the film's sprawling themes, Pattinson continues to prove himself perhaps the most interesting leading man to have appeared in the Twilight films.

Sharing with my comics group. Thx.