I was interviewing political comedian Jena Friedman recently when I asked her what was on her side table. She responded, The Weimar Years by Frank McDonough. "Light reading, huh?" I joked. She paused, then said, "Oh, I'm really fascinated by the Weimar Republic. Always have been." Another pause. "But especially now."

“Especially now.” Those two words pushed me to understand what she was seeing that I was only beginning to recognize.

In Weimar Germany, antisemitic ideas had to spread through physical networks—forged documents like the Protocols of the Elders of Zion passed hand to hand, Nazi newspapers requiring actual printing presses, Hitler's speeches reaching maybe tens of thousands through radio. The machinery of hate was constrained by geography, by technology, by the simple physics of distribution. It took years to mainstream these ideas, to normalize them, to make them seem reasonable to ordinary people..

But now? I can watch it happen in real time on my phone. An influencer spreads misinformation about Jews to millions of followers with a single post. A conspiracy theory reaches more people in an hour than the Protocols reached in a decade. We're conducting a real-time experiment in mass manipulation at a scale that Goebbels would have gobbled up with glee.

The metaphorical Weimar of today isn't a single struggling republic. It's every smartphone, every social media feed, every podcast that reaches millions of people hungry for content. And just like then, most people spreading this stuff don't even realize what they're doing. What are the implications of such a wide scale campaign?

I was scrolling through Instagram recently when this reality crystallized for me. Comedians like Theo Von, Tim Dillon or Adam Friedlander with millions of followers suddenly become “passionate” participants in the Israel-Palestine debate, entertainers who never showed interest in Syria, Yemen, Myanmar, or Sudan, but who stumbled into geopolitical influence without any expertise or responsibility. Why this conflict? Why do people who couldn't find the West Bank on a map suddenly have such strong opinions about Jewish self-determination?

I’ve written about this before, but it bears repeating. The obsession with Israel isn't purely regional or political—it taps into something much older. There's a deep, historically proven fixation on Jews that transcends geography or rational proportion. The disproportionate focus on the world's only Jewish state, the unique scrutiny applied to every Jewish action, the way Israeli policies become global causes while actual genocides get ignored—this isn't coincidence. It's pattern recognition. As Nicholas Kristof wrote in an editorial titled "Where There's No Debate About Genocide — and No Response, Either," "As debate boils over allegations of genocide in Gaza, there's another place where all sides in the United States seem to agree a genocide is underway — yet largely ignore it." Yet Kristof never attempts to resolve why this is so, though I suspect he knows. My mother always said: no Jews, no news. Which helps me now understand what Friedman meant by "especially now.” We're watching that ancient obsession find its perfect amplification system and all you need to do to participate in it is to “like” it.

A few nights ago, Chris Martin called two audience members up on stage during their show at Wembley Stadium. When he asked where they were from, they told him, and the crowd of 90,000, that they were from Israel.

"OK…well, well," Martin said, clearing his throat. You could practically see his mind at work like that GIF of the blonde woman with math equations circling her head. Whatever he said next would land him in hot water with one of two involved demographics and he obviously picked offending the smaller one. The sellout crowd was already starting to boo—not because these were bad people, but because they were Israeli. "Well listen," Martin continued, "I'm gonna say this. I'm very grateful that you're here as humans, and I'm treating you as equal humans on earth, regardless of where you come from or don't come from. Thank you for being here, and thank you for being loving and kind."

He put an arm around one fan, then continued: "And though it's controversial maybe, I also want to welcome people in the audience from Palestine. We have, we are, I believe we're all equal humans." I’ve watched this clip more times than the FBI watched the Zapruder film.

Martin, like so many well-meaning celebrities, is a puppy-eyed doofus. I would never qualify him as particularly articulate (see: all of his lyrics), and he's not known for his political sophistication. But something about how he said this, the need to explicitly state that Israelis are "equal humans," the way he had to balance their very existence with Palestinian acknowledgment made me wonder if there was a throughline from the content he's been absorbing over the last two years. Has social media's relentless, punishing focus on Israel unconsciously affected even those who would never assume they'd be influenced by such things? Even the singer of a band whose latest single is titled “ALL MY LOVE” in, yes, all caps?

When did Jewish existence become something that needs to be justified at a pop concert? When did simply being Israeli require a disclaimer? When did the guy who sang "look at the stars, look how they shine for you" start qualifying who belongs under those same stars?

This moment revealed something profound about how deeply this propaganda has penetrated. Martin wasn't being deliberately antisemitic. If so, he would have hated his own wife, a convert to Judaism, for the ten years they consciously coupled. This was Coldplay’s frontman trying to be fair, balanced, inclusive. But the very framework he used, the need to treat Israeli humanity as controversial, shows how the conversation has already been shaped by forces he probably doesn't even recognize. The crowd's immediate booing of two young women simply for being Israeli demonstrates how successful this campaign has been at dehumanizing Jews on a mass scale.

What struck me wasn't only Martin's response. It was how automatic the crowd's hostility was. Ninety thousand people instantly knew which side to take when Jews were involved, even at a pop concert that had nothing to do with politics. This is what propaganda looks like when it works: not conscious hatred, but unconscious bias so pervasive it feels natural. For all of Coldplay's songs about healing and fixing what's broken, some things can't be fixed. Sometimes the lights don't guide you home.

This selective attention takes a psychological toll that I don't think non-Jews fully understand. In Bojack Horseman’s creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg's new Netflix series Long Story Short, there's a scene that crystallized something I'd been feeling but couldn't articulate. A character named Avi responds to his sister's accusations of "internalized antisemitism" by explaining why he drifted from Judaism: "Judaism was suffocating. We had to learn another language. Only be with people like us. Eat fish that looks like a brain. Be afraid all the time. All those stories about the Holocaust. The Inquisition. Learning that everyone hates you and wants to kill you doesn't exactly make for a well-adjusted person."

Even the cartoon Jews get it. The exhaustion of carrying that weight, of being told from childhood that you're perpetually at risk, that hatred of your people is a historical constant you must always be prepared for. Having dinner with my British cousins last week, we talked about how we're all afraid in ways we never expected to be. The conversation kept circling back to the same questions: How did we get here? When did it become acceptable to boo Jews at concerts? How do we explain this to our children?

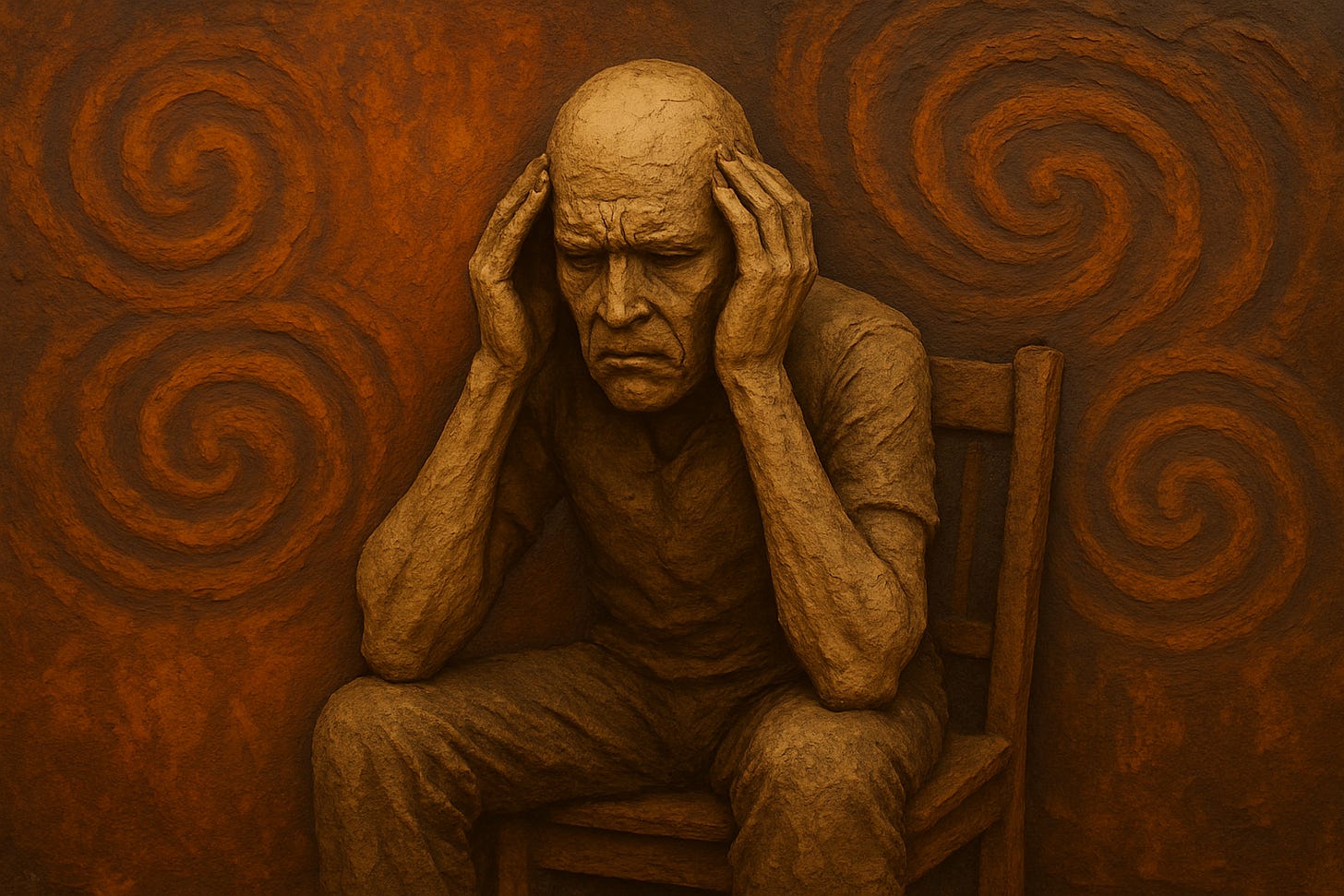

But as we shared stories and fears, I realized what's been overtaking me lately isn't fear—it's exhaustion. Deep, sustained, all-consuming exhaustion. I'm tired when people ask me about Netanyahu, as if I'm personally responsible for every Israeli government decision. As if I can do anything to change his war-mongering ways. Every Jew I know gets these questions; we're all expected to explain why antisemitism keeps finding new champions, to defend or condemn politicians who weaponize our anxiety for political gain. These conversations always position us as either defendants or expert witnesses in cases we never wanted to be part of.

My friend and renowned therapist Noam is reading a book called Hatred by Dr. Willard Gaylin, who describes how raw personal passions transform into acts of violence and cultures of hatred. Gaylin argues that hatred goes beyond mere emotion—it's a psychological disorder, a form of quasi-delusional thinking that requires "a passionate attachment," an obsessive involvement with a scapegoat population. It allows angry and frustrated individuals to disavow responsibility for their own failures by directing blame toward convenient victims.

But Gaylin also cites Aristotle's crucial distinction between anger and hatred: "Whereas anger arises from offenses against oneself, enmity may arise even without that; we may hate people merely because of what we take to be their character... Moreover, anger can be cured by time, but hatred cannot... And anger is accompanied by pain, hatred is not."

Reading about this distinction helped me understand what I've been feeling. What many Jews are experiencing right now isn't hatred—it's exhaustion accompanied by deep pain. We're tired from specific offenses, worn down by having to constantly justify our existence, our right to safety, our connection to Israel. Unlike hatred, this exhaustion can be addressed, can be relieved. But it requires acknowledging that the constant demand for explanation and justification is taking a toll.

The frustration isn't just about being misunderstood. It's about being perpetually cast in roles we never auditioned for. Every conversation becomes a performance where we have to prove our humanity, defend our complexity, explain why we deserve the same consideration given to others without question. It’s sad to say, but most Jews I know have become professional explainers of our own right to exist.

Last night I saw industrial rock act Nine Inch Nails at Barclays Center, and something shifted. When 15,000 people yelled "If there is a hell, I'll see you there!" in unison, I felt something loosen in my chest that had been clenched for months. I've been a fan of mastermind Trent Reznor's three decade project for years but had never seen him live. What I've always admired most about his music is how it feels urgent and visceral while remaining vague and agnostic enough that you can use his songs as a canvas to paint your own frustration onto. Reznor rages against systems, against feelings of powerlessness, allowing each listener to fill in their own sources of exhaustion.

I remember as a child feeling wholly uncomfortable by Reznor's aggressive lyrics, especially in "Closer,” oddly his biggest hit. The inappropriateness and raw intensity was beyond what I was willing to process as a kid. But there were other songs that spoke to something deeper, like when he screamed in my ears about believing he can see the future because he repeats the same routine, thinking he used to have a purpose but that might have been a dream. He was articulating the feeling of being trapped in cycles, of living where meaning felt elusive, of being worn down by systems beyond your control.

Watching a 60-year-old man scream anthems of frustration, as I did the other night, shouldn't work. By definition, it defies what that kind of emotional release is supposed to be. Cathartic music is usually the province of youth—teenagers processing feelings they can't yet name. By 60, you're supposed to have found peace, acceptance, maybe even wisdom. You're supposed to have let go of that need for raw release.

But Reznor validates these feelings that we're told to outgrow. He proves that sometimes the exhaustion doesn't disappear with age, and maybe that's okay. Maybe some things are worth staying frustrated about, even if the world tells you to move on, grow up, find perspective.

For two hours, I had a place to put all this weariness I've been carrying. The exhaustion of watching propaganda spread through entertainment platforms. The fatigue of needing to justify Jewish existence at pop concerts. The burnout of feeling afraid in ways my parents' generation hoped their children wouldn't have to. And this morning, I woke up feeling different. Not completely peaceful—the problems remain. But less consumed, less raw. The exhaustion hadn't disappeared, but it found somewhere to go besides circulating endlessly in my head.

Maybe that's what I've been learning: frustration isn't inherently destructive if you don't let it become your permanent address. It can be a signal, a motivator, a way of honoring that something genuinely wrong is happening and you refuse to normalize it. The key is finding ways to release it that don't leave you emptier than when you started.

All of this is genuinely exhausting. The question isn't whether I should be tired. It's what I do with that fatigue once I've acknowledged it. I don't have complete answers yet. But I know that pretending everything is fine when it clearly isn't would be a betrayal of something essential. And I know that two hours of screaming along to industrial music in a room full of strangers somehow helped me process feelings I couldn't work through on my own.

The goal, as I’m learning, isn't to stop being frustrated about things that deserve frustration—it's to find ways to live with that weariness without letting it destroy everything else that matters. Sometimes you need to scream into the void, not from anger, but from the simple human need to be heard. Sometimes you need to tell the forces trying to erase you, as Reznor did: 'I'd rather die than give you control.' Control over how we see ourselves, how we move through the world, how loudly we're allowed to exist. Now, bow down to the one you serve. You’re going to get what you deserve.