“We ate the food, we drank the wine, everybody having a good time, except you... you were talking about the end of the world." - U2, "Until the End of the World"

I've heard this song hundreds of times, but when it played on the radio this morning, those lyrics elicited a new reaction out of me. There's something hauntingly familiar about that person Bono describes—not because it's me, but because I recognize the archetype all too well. The doomsayer at the dinner party, the one who can't let a moment of joy pass without reminding everyone about the looming apocalypse.

What struck me wasn't just the recognition of that personality type. It was my own growing fear of becoming that person. Recently, I've felt the gravitational pull of that pessimism myself; the temptation to surrender to a kind of preemptive grief about the state of things. After all, when you expect the worst, you're either right or pleasantly surprised. It's a form of emotional insurance.

It's hard to ignore that we're steeping in a culture of carefully curated despair. I've written before about television's sadness problem, or how the job market isn't exactly a ray of sunshine either. Even our media ecosystem seems designed to maximize dread. Every headline comes with a side of apocalypse, every notification another prophecy of doom. I haven't even mentioned one of the greatest hitmakers of our time releasing a song titled "Heil Hitler."

The result is a peculiar cultural condition, a kind of anticipatory grief for a world that hasn't ended yet. We're mourning possibilities that haven't even been foreclosed. We're eulogizing institutions that, while flawed, are still standing. We're writing obituaries for species that are still hanging on, democracies still functioning, communities still connecting.

But here's what I've been wrestling with: I don't want to live that way. I refuse to become the person who can't enjoy the wine and the food because I'm too busy prophesizing disaster. I want to maintain hope without delusion, to acknowledge challenges without surrendering to despair. I want, against all odds, to be an optimist. But optimism doesn't just feel difficult—it feels impossible. Which, yes, I realize, is exactly what a pessimist would say.

Which, naturally, brings me to my kids' recent obsession with Parks and Recreation.

For the past month, Edie and Eleanor have been binge-watching all seven seasons of Parks and Rec. I've always considered the show a bit too cutesy, too earnest for my taste. I'm more of a 30 Rock guy—give me one-liner pile-ons and bitingly sarcastic asides. Nevertheless, I've found myself drifting into the family room, assuming that classic dad position, half-watching while pretending to do something else entirely, and somewhere along the way, I realized something special about Amy Poehler's Leslie Knope.

It wasn't her manic energy or her borderline-creepy binder obsession. It was her unflinching, almost pathological optimism. In the face of bureaucratic roadblocks, small-town apathy, and outright hostility, Knope remains convinced that local government can improve people's lives. When circumstances conspire against her (which they do, repeatedly), she doesn't sink into cynicism. She recalibrates, she pivots, she finds another approach.

I began to understand that Leslie Knope isn't an optimist because things are going well. She's an optimist because she believes in her capacity to affect change, especially when things aren't going well. Her optimism isn't a mood. It's a methodology.

Every so often, I'll pop in on Yale academic Dr. Laurie Santos and her podcast The Happiness Lab. Recently, she interviewed Dr. Sue Varna about her 2024 book Practical Optimism, which argues that optimism isn't some inborn personality trait but a learnable skill, one that yields tangible benefits in terms of health, longevity, and success.

Varna's concept represents the fusion of two seemingly opposing ideas: a mindset that believes in the limitless positive potential within oneself and others, combined with mastering behavioral skills that lead to healthy decision-making. It's optimism with guardrails, hope with a GPS.

The research is compelling. Optimists experience more happiness and success, plus they enjoy physical health benefits from better cardiovascular outcomes to enhanced immune function. A 2019 study even found optimism associated with an eleven to fifteen percent increase in lifespan. The kicker? While optimism has genetic components, its advantages don't solely come from having a naturally sunny disposition. They come from specific habits and coping skills, things we can learn.

In her writings, Varna also mentions journaling, that wellness panacea prescribed like meditation's practical cousin. I've tried it, of course. But somewhere between my third and fifteenth gratitude list, I started feeling like I was typing fortune cookie messages to myself.

The experts insist regularity is key, but there I was, day after day, being thankful for my family, my friends, my home. But with each entry, each acknowledgment of blessing, I found myself increasingly aware of the flip side: how much I have to lose, how many precious things require protection in an increasingly hostile world. My gratitude journal was inadvertently transformed into an inventory of vulnerabilities.

Which made me wonder: Why is optimism so hard for me? Is this a personal failing? Or is there something larger at work? Something woven into the fabric of my identity, my history, perhaps even my DNA?

"There is a crack in everything / That's how the light gets in." - Leonard Cohen

Judaism carries a complex relationship with optimism, one tempered by centuries of exile, persecution, near-annihilation, and existential precarity. For many Jews, optimism can feel like an emotional risk. Or even a betrayal.

A friend and I were discussing home renovations when he made an aside that has lingered with me: "Maybe it doesn't make sense to invest in my home here, because who knows how much longer we'll be welcome in this country." He delivered it as a dark joke, with that familiar Jewish gallows humor, but it settled in my heart and unnerved me.

That's the thing about Jewish pessimism, it's not irrational. It's historically informed. When your family photo album has empty pages where relatives who died in pogroms or concentration camps should be, caution becomes a form of intelligence.

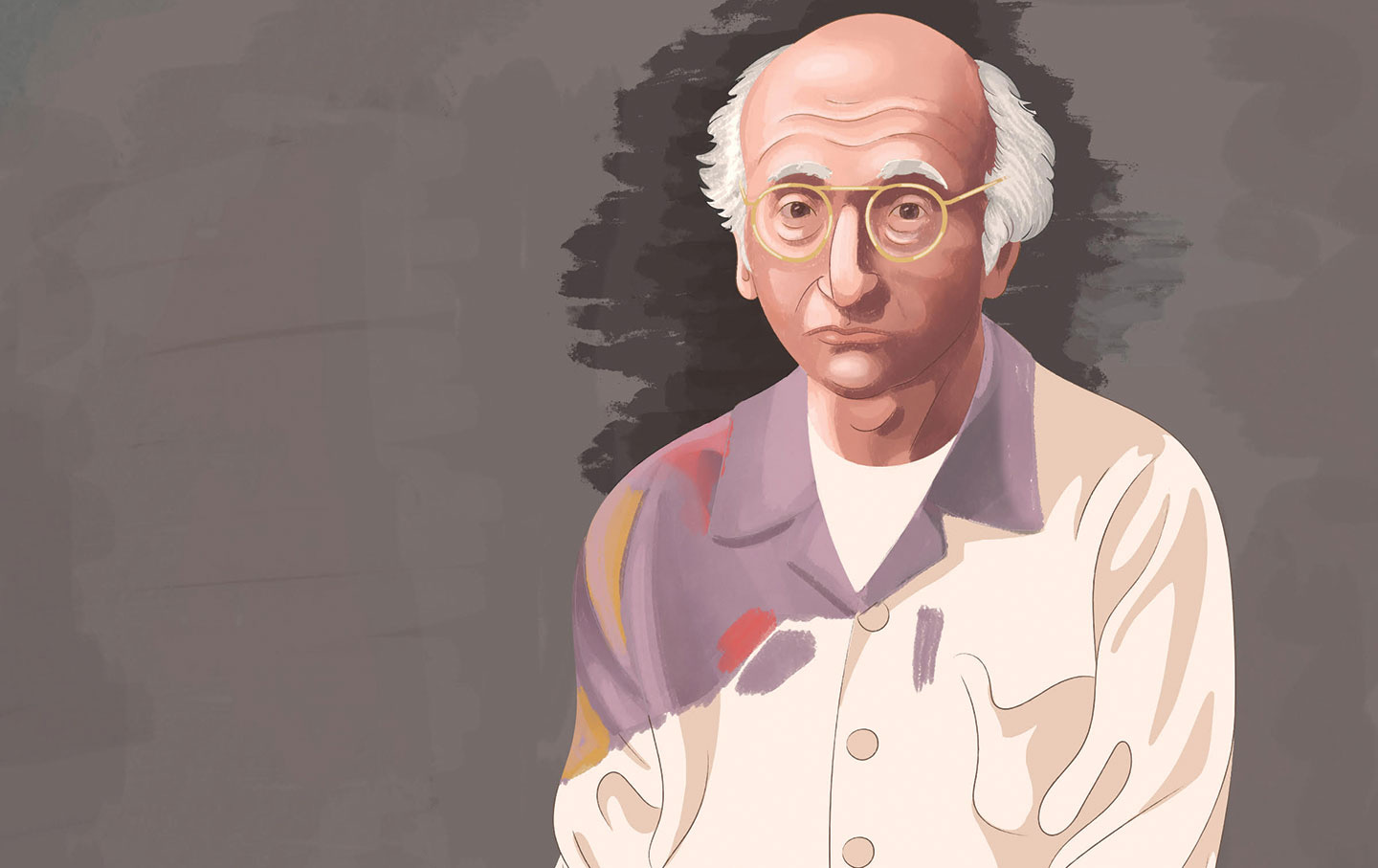

American culture has long depicted the Jewish man as an eternal pessimist. Think Woody Allen's neurotic persona, perpetually anticipating catastrophe, or Larry David's exquisite articulation of grievance. These portrayals aren't accidents. They're built on a foundation of collective memory and learned caution. Our cultural touchstones have been predominantly men who expect the other shoe to drop, who find comedy in catastrophizing because if you don't laugh, what's the alternative?

Dara Horn's book People Love Dead Jews argues that Western culture has a strange affection for Jewish death but no patience for Jewish life or joy. "The world wants the Jew to die nobly, not to live awkwardly," she writes. It suggests that optimism itself can be a subversive Jewish act—that choosing joy is a form of resistance. Elsewhere, Horn writes for the Sapir Journal in an article titled “Dreams for Living Jews,” “I now have a very different attitude toward the Jewish past and present. One need not dismiss or minimize the “lachrymose” realities of Jewish history to perceive and marvel at its joys and triumphs; on the contrary, the blessing and the curse are entirely intertwined, because the astonishing power of the Jewish past and present is not merely this culture’s endurance or even its objective achievements, but precisely its astonishing resilience, its constant reinvention, its demonstration of what might be possible. That reinvention was not foreordained or predictable; it required hard work and harder optimism about the existence of a future.”

I think about my grandparents, Holocaust survivors who nonetheless built new lives in America. Their optimism wasn't boundless. It was practical, cautious, always tempered by awareness. They came to this country carrying nothing but the heavy sorrow in their eyes. But they also planted gardens, opened businesses, raised children. They chose life despite having every reason not to.

Dr. Rachel Yehuda's research on intergenerational trauma in Holocaust survivors suggests that trauma can be biologically inherited. But she's also quick to emphasize that "our biology is not our destiny. Awareness creates a pathway for change." If trauma can be inherited, maybe resilience can be too. Maybe that's what my grandparents were giving me alongside their caution, a template for continuing despite everything, an ancestral whisper that survival itself is an act of defiant optimism.

My ADHD brain has also been thinking about the 2023 film Everything Everywhere All At Once (okay, get your eye rolls out of your system) inspired by a stunning and vibrant Murugiah poster that arrived this week for my home office, an explosion of color with that infamous everything bagel at its center (see below). My kids were immediately drawn to it, asking what that swirling black hole of sesame seeds represented.

How do you explain to children that the everything bagel is a visual metaphor for nihilism? I’ve tried to explain this to adults with little success. I stammered something vague about "big feelings" and promised we'd watch it together when they're older and ready for dueling sex toys.

But I should have just spoken with them like a Park Slope parent explaining systemic inequality over brunch: "Kids, this everything bagel is actually the perfect emblem for our current moment; a visual metaphor for the crushing weight of existential nihilism in an age of information overload. We're all staring into these sesame-coated vortexes of political chaos, climate collapse, and technological upheaval, watching helplessly as meaning itself gets sucked into the void. Now, who wants Cheez-its?”

What makes the Daniels' film so profoundly hopeful is its rejection of nihilism as the final answer. In a universe of infinite possibilities, the most radical act isn't surrendering to meaninglessness but choosing meaning anyway. Creating it through connection, through kindness, through a stubborn insistence that some things matter even when nothing has inherent meaning.

There's a duality in the film that mirrors my struggle with optimism. Evelyn Wang, portrayed by Michelle Yeoh, isn't an optimist by nature. She's weary, frustrated, prone to seeing what's missing. But when faced with infinite evidence that nothing matters, she makes the counterintuitive choice: to care anyway, to fight anyway, to love anyway.

That's the practice I'm trying to develop. Not the blind optimism of someone who hasn't seen the darkness, but the earned optimism of someone who has looked directly at it and chosen differently. The glass isn't half full or half empty—it's both, simultaneously. The trick isn't pretending we don't see the emptiness; it's acknowledging it while still valuing what remains.

I started this essay with U2's "Until the End of the World," a song about the tension between enjoying life and recognizing its precarity. We're all trying to eat the food and drink the wine while that persistent Larry Mullen Jr. drumbeat plays in the background. But maybe the challenge isn't learning to dance despite the drumbeat—it's reconceiving what that rhythm actually represents. What sounds like a countdown might actually be a universal heartbeat, a pulse signaling not collapse but continuation, not ending but endurance.

In the multiverse of possible selves, it’s not easy to be the one who recognizes the darkness but redefines what it might mean. Because transforming alarm bells into wake-up calls is more liberating than surrendering to someone else's soundtrack. Because sometimes the most radical act isn't bracing for impact but daring to believe we're hearing the opening notes of something new.

That's practical optimism. Not a guarantee, but a choice. Not a prediction, but a practice. Not a feeling, but an act of will. And like any practice, it can start small. Before checking the news each morning, before scrolling through the digital catalog of catastrophes, I've started asking myself one question: "What might go right today?" Not everything. Not forever. Just today. Just one thing. It's hardly revolutionary. But maybe that's the point. The world doesn't need more people who can perfectly articulate why we're doomed. It needs more people who can tell those people it’s going to be okay. And the thing is, between us…? They don’t even have to mean it.